All Rights Reserved © "Never argue with a fool; onlookers may not be able to tell the difference."

- Mark Twain I check the comments on this blog regularly. The idea is that we're going to have a conversation about the ideas I've presented. You should be aware of the fact that when someone emails me an interesting comment, the odds are good that I'll post that in the comments anonymously and reply to that comment on the blog rather than in email.

Dec 25, 2016

Catching Up

Dec 19, 2016

Making A Dangerous Bed

All Rights Reserved © 2012 Thomas W. Day

(First Published in Rider’s Digest #189, June 2015)Back in my Colorado days, I used to hang out with a trio of guys who had a variety of motorcycle skills. The leader of the pack was Brett, a guy who practically grew up on motorcycles and who is one of the nicest, most patient and loyal people I've ever known. I have considered Brett my best friend for two-thirds of my life, even though I haven't seen him more than a couple of times in the last ten years. David was a newbie to motorcycling, but he had taken an MSF course and had a pretty good grip on his skills and physical and mental limits. Richard was slightly less new to motorcycling than David, but had started off thinking motorcycling was going to come naturally to him and discovered it didn't. He'd crashed his bikes a couple of times, trying to keep up with Brett and me, and had moved from overly confident to massively paranoid. By that time, I'd been riding for twenty-five years and had way more confidence than skill. I'd moved to Colorado from California by myself and was wallowing in my independence and a relatively responsibility-free, semi-single-guy life. So, my moto-motto was "Shut up and ride." I even wore a t-shirt with that printed on the front and back.

One "feature" of this collection of diverse skills was an assortment of different start-up times for a ride to anywhere. If we were going to ride to downtown Denver for coffee, it would take anywhere from five minutes to an hour-and-a-half for the four of us to be ready to roll: five minutes for me and ninety minutes for Richard, for example.

One weekend, we decided Pikes Peak needed climbing one more time before the mountain riding season ended. Brett and I did most of the planning and we picked a filling station on the south end of Aurora for the rendezvous. Our start time was 7:00AM with some margin to accommodate the late risers and slow movers, but 8:00AM slipped by with one of the guys still "on the way." The first part of our route was going to be Parker Road (Colorado Highway 83) south to Colorado Springs. It's about 80 miles, via 83, to Colorado Springs and another 35 miles to Pikes Peak Park through some backroads around the Springs. Two-and-a-half hours on a slow day. Once you got into the park, the old road was 19 miles of beautifully unpaved twisty mining trail to the top. (This year, they finished widening and paving the whole thing and there is no more point in seeing the damage done than there is hoping that Newt Gingrich is married for life, this time. When the Peak was unpaved it was "America's Highway." Now, it's just a tourist path.) We had a breakfast plan for Colorado Springs, but with the late start Brett and I decided to move the meal to the café at the top of the peak. An hour after our start time, we had a mild disagreement about waiting or going.

Since I hadn't planned on plodding along at the pace the two newbies would be setting, I decided to meet them at the park. We'd done this a dozen times in the past and Brett and I sorted out where we'd be about when and agreed that if the pack didn't catch up to me at the base of the park by 11:00AM, we'd meet at the top. That settled, I hit the road. I'd loaded camping gear and a change of clothes, in case I decided to take the long way home after the Pikes Peak trip. I took a few deviations from the short route to the park, hoping that the guys would catch up or pass me. Still, I arrived at the base of the park on time and waited a half-hour in the tourist center before I bought a pass and headed up the mountain. We had some late season rain that year and the road was pretty torn up from traffic and erosion, so it was in perfect condition and I pretty much had the Peak to myself. I got to the top pretty quickly, for me, and figured I had an hour or two to myself before the pack arrived.

My bike, a 1992 Yamaha 850 TDM, was coated from the wet road and my chain was bone dry and caked in clay. I found some rags in the tourist trap's dumpster and filled a milk bottle with water to get started on some maintenance. I scrubbed off the muck from the chain and gave it a WD40 rinse before applying fresh chain oil. It didn't need it, but I went through the chain freeplay adjustment routine. After cleaning up the frame and engine, I made the rounds of all the fasteners, making sure everyone was in place and tight. I was parked right on the edge of the old tourist center's parking lot, so the workshop view was spectacular. I pulled the air filter, which was clean, and reapplied some fresh filter oil for no reason other than that I had it out and I had the oil with me. Short of checking valve clearances, I'd done everything I could think of to the bike.

So, I went back into the tourist center and had breakfast; a couple of donuts and a large cup of coffee. I walked out back and got into a conversation with a cog railroad conductor about the first and last train trip of the year, which often involved pushing a lot of unexpected show up or down the track and a lot of scared passengers. He went back to work and I was bored.

As long as you don't exit the park, you can ride up and down the mountain all you want for your park pass. So, I decided to ride down the mountain and meet the guys on their way up. I did that, twice, and, still, they weren't anywhere to be found. In 1992, none of us had cell phones so calling wasn't an option. I wasn't really worried, but closing time was approaching and I didn't want to be stuck on the mountain in the dark. Finally, just a few minutes before the visitor center closed, the three guys rolled into the lot. Brett looked pissed. I couldn't figure out the other two guys' expressions.

It turned out that, in spite of the late start, Richard and David insisted on stopping for breakfast, which burned an hour-and-a-half. After eating, they plodded along at a barely faster than walking pace until they got to the park. To "celebrate" riding the mountain, before they'd ridden the mountain, they stopped at the park store and bought "I Rode the Peak" patches for their jackets. Once they started up the mountain, the pace slowed even more. The switchbacks, the wheel ruts, the deep drainage ditch on one side and the steep drop-offs on the other combined to make the last few mile sheer terror for Richard and David. Brett stuck with them, dedicated friend that he is, and had about as much fun riding the mountain as he would have had in a dentist's chair; although the chair might have been a faster ride.

As they rolled into the lot, a park ranger was herding the straggling tourists to their cars so he could close the lot's gate. The guys didn't even have time to take off their gear before they were being hustled off of the summit and back down the mountain. That might have been a good thing, since riding downhill scared is much worse than riding uphill and they didn't have time to work up a good batch of fear before they were on their way down the mountain. The first few miles were the roughest, especially with the road in end-of-season condition and some pretty energetic bursts of wind near the top. They paddled around the sharpest of the corners and I took up the rear so that Brett could at least go down the mountain without herding sheep all the way. After we left the parking lot, I shut off my motor and coasted behind the guys, stopping every mile or two to let them get a ways ahead of me so that I could collect enough momentum to roll through corners without having to push. It took a good bit more than an hour to get to the park entrance. The gate was closed, the park was abandoned, but it was easy enough to get the bikes around the barrier. Just before the park road merged into Manitou Avenue, I saw Brett parked just off of the road. He was in much better humor, since he'd had time to find an ice cream shop and had drained a large milk shake while waiting for us to crawl down the mountain.

It was dark and riding back home via I25 was the only practical option, since Parker Road would be filled with deer and antelope for the next few hours and none of us was up for picking antlers out of our teeth. The guys settled for finding a cabin in Manitou Springs for the night. I was all for snagging a campsite in Garden of the Gods or just heading out Colorado 24 for Buena Vista and finding a campsite where ever one turned up. David and Richard convinced me that I wanted to hang with them for the night by insisting that they would cover the cost difference between a campsite (free, if I camped between Manitou and Buena Vista) and the cabin. Like an idiot, I became a follower.

They had a cabin site in mind and found it quickly. It was a two bedroom cabin with two fold-out beds in the huge living room. I took one of the living room beds. Our plan was to get the room sorted out and walk to a nearby restaurant for dinner. So, I was going about that when I dropped the damn bed on my left foot. I was pulling out the frame, expecting it to swing up before it lowered to the floor. Instead, the bed shot out about two feet and dropped like a spring-loaded anvil; right on my big toe. I'd pulled off my boots at the door, so there was nothing between my foot and that assassin's weapon and it almost amputated my toe.

In moments, the toe turned black. It was bleeding like a stuck pig, so I used up all of the stuff in my medical kit to medicate and bandage the bit toe to it's nearby partner. We went to dinner, me shoeless on my hobbled foot. I drained a bottle of some kind of painkiller to try to sleep that night and woke up to find that the toe nail had lifted off of the toe, in spite of my having drilled a neat pressure-letting hole in the nail and taped it tight before I went to bed. I could not get my left boot on, so I had to cut the boot and gaff-tape it together; once my foot was in it. Walking was miserable and awkward. Shifting was painful and had to be done with my whole foot or heel. Buena Vista was out of the question. Getting back home would be an achievement.

We had breakfast in Manitou Springs. I set out ahead of the guys under the assumption that they'd probably catch me and, if I ended up stuck on the side of the road unable to ride, we'd work out a plan to get my bike and me home. Once I hit the interstate, I was pretty sure I'd make it home and that didn't turn out to be a problem. The next day, my doc pulled the toe nail, stitched a patch over the exposed toe, and put my toe in a brace that would be my hobbling partner for about two weeks. The bone at the end of the toe (distal phalanges) was crushed.

For the next several months, I took a lot of crap about being the "big bad bike racer who was crippled by a hide-a-bed." Obviously, the real reason I ended up crippled was that I stayed back to be a nice guy and escort the slow guys down Pikes Peak. Not only do "nice guys finish last," but they might even get hurt for the effort. Screw being nice. "Shut up and ride."

Dec 18, 2016

My New Career

Dec 17, 2016

TurboBike, When You Know You’ll Never Grow Up

“Turbospoke is a complete exhaust system that fits to any bike and makes it look and sound just like a real dirt bike. Turbospoke is based on the old 'baseball-card-in-the-spokes' concept, brought right up to date. The realistic engine sounds are created using long lasting plastic cards, a clever sound chamber and an awesome megaphone exhaust pipe which really amplifies the sound.” Sounds more like a drawn-out fart than a motorcycle engine, but . . . I guess that’s a “real motorcycle sound” if a Harley is a real motorcycle.

Dec 14, 2016

Is This Like the Others?

During the parade season, there is never a shortage of noise makers in

Lucky for me, Red Wing has a decent Suzuki and Yamaha dealership, but I don’t know why. The dealership seems to retain the same collection of “new” and used bikes for at least a couple of seasons, probably until another dealer or wholesaler takes them off of their hands. If it weren’t for boats and ATVs and snow machines, I suspect we’d lose that dealer. The Polaris/Victory dealer never seems to have customers and I’d guess someone is burning up a trust fund with that venture. Likewise, the local community college offers a summer full of motorcycle safety classes, but 3 out of 4 of my last season’s MSF classes cancelled due to lack of interest, including an Intermediate Rider Course that wasn’t supposed to cancel under any conditions. On a typical work day, it’s rare to see more than one of two bikes on the road and most of those will be touring riders passing through town.

It’s a mystery. Red Wing and the surrounding territory is a massive riding resource. We have twisty roads and small towns with history and good food and recreation. You can’t beat the river valley for upper Midwest scenery; it’s the closest thing to mountains we have for 650 miles. As a mostly-dirt rider, I have more interesting country roads and marginally maintained back roads than I know what to do with. It is incredibly easy for me to burn up a tank of gas in an afternoon without doing more than crossing pavement every 50 miles. There is even a few sections of actual off-road riding from abandoned farm roads that haven’t yet been converted to farm land.

Outside of the summer pirate parades, it feels like motorcycling is on its last legs here. All of the riders I know are over-50 and most of them are on the edge of giving it up. The kids I meet who talk about buying a bike and learning how to ride just talk about it. It’s not a practical thing for them, for whatever reason. There is some off-road activity in Elsworth and I should get over there to check it out. But . . . it’s Wisconsin and a battlefield of starving small towns and bankrupt counties all overstaffed with highway patrol and sheriff’s deputies haunting the backroads to make their quotas. I cross the river only when I really need to.

Dec 12, 2016

#137 Foot Out, Rider Down

All Rights Reserved © 2014 Thomas W. Day

A friend sent me a note this week, complaining about the godawful scooter and bike skills he witnessed near the UofM. He said, "When I was instructing, a favorite thing to yell at students (and sometimes regular folks) was 'pick up your feet'. For some reason that horrible habit has re-entered the consciousness of people that think they know how to ride. A few days ago I watched a young guy on a scooter (wearing a helmet, with shorts and flip flops) stick his left foot out as he arced through the intersection. This evening I watched a young hipster (flannel shirt, rolled up jeans with lace up boots) on a Sportster leave an intersection making a left turn with his boot out like he was at the Springfield Mile. Just a few blocks later, I watched an overweight middle age guy on some bloated metric cruiser wobbling away from a stop sign with his feet down as he tried to gain momentum and stability. Unfortunately he too was wearing flip flops. At that point I was ready to stick my head out and yell."

Dec 10, 2016

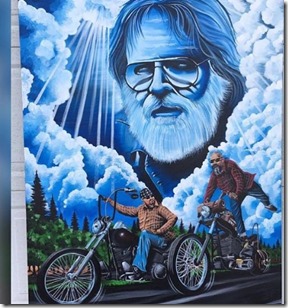

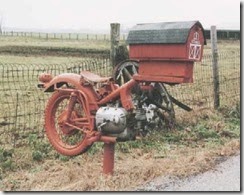

Form over Function = Art

So, for 49 years we’ve lived together with disparate interests and conflicting styles. Art, as I define it, comes from an old Greek (or Chinese or Abo) word meaning “not good.” If something is art, the execution will be amateur, the choice and use of materials will be juvenile, and purpose will be obscure or nonexistent. My wife and her artist friends are convinced that I’m too obsessed with purpose and artisanship (an insult, to the art crowd). I’m convinced that if the workmanship sucks, I don’t care about the rest. When I look at a piece of ironwork art, I look at the welds first. If they are amateur, poorly formed, or ground off to hide the poor workmanship, I don’t take the rest of the work seriously. Same for woodworking. I’m looking for a level of workmanship before I start considering the form. As a mediocre musician, I have always required music to be something more complicated than I can perform if I’m going to spend my money on it.

The fact that this motorcycle is unrideable except under the most restricted conditions defines it as art and not a functional vehicle, in my mind. I’m a big fan of engineering, like the KTM at the beginning of this essay and not much of a fan of cobbled and useless art, like this cruiser. I’m not bragging here. I realize that this function-over-form requirement limits my ability to appreciate purely form-based art. I don’t see anything but discomfort, impracticality, and unnecessary complication and expense when I see a bike like this cruiser. I don’t have a mechanism that allows me to appreciate it as art alone.

A designer/author named Don Norman sums up my problems with bad design (art) in his book, The Design of Everyday Things, “Two of the most important characteristics of good design are discoverability and understanding.” Motorcycles, for example, are dangerous, complicated, and non-intuitive (countersteering, for example). Good design would minimize that. Lousy design adds to all of the negatives without providing any value, other than chaos, to the rider. And if you’re not riding your motorcycle, you are not a motorcyclist but an owner of a piece of art.

As Norman said about Apple products in a FastDesign article a while back, “Apple is destroying design. Worse, it is revitalizing the old belief that design is only about making things look pretty. No, not so! Design is a way of thinking, of determining people’s true, underlying needs, and then delivering products and services that help them.” Likewise, motorcycles with a primary purpose of “looking pretty” are destroying motorcycling by convincing rube motorcyclists that looking cool (or clownish, depending on your perspective) is more important than going places safely and competently. These toys are so badly designed that they need to make as much noise as possible to compensate for the fact that the riders are helpless to defend themselves with the qualities a decently designed motorcycle and motorcyclist take for granted; agility.

Wow! If I were in a better mood, I’d go back and pare this down to one argument. I’m not in a good mood and probably won’t be for at least 4 years. The worship of ignorance, chaos, and corruption has become a national religion and I don’t expect to enjoy it any more than I like looking at a piece of badly executed “art.”

Dec 9, 2016

A Room Full of Elephant

Way back in 2008, I wrote an MMM article titled “Hearing Damage and Motorcycling.” Among other things, that article produced one of the looniest, most illiterate responses anything I’ve written for anyone has ever inspired. This month, Cycle World discovered that motorcyclists are among the world’s most deaf recreationalists. The article, aptly titled “Say What?” by John Stein, concludes that “Hearing damage is motorcycling’s elephant in the room.”

Way back in 2008, I wrote an MMM article titled “Hearing Damage and Motorcycling.” Among other things, that article produced one of the looniest, most illiterate responses anything I’ve written for anyone has ever inspired. This month, Cycle World discovered that motorcyclists are among the world’s most deaf recreationalists. The article, aptly titled “Say What?” by John Stein, concludes that “Hearing damage is motorcycling’s elephant in the room.” Dec 7, 2016

Bikes I've Owned and Loved (a lot or a little): 1971 Kawasaki Bighorn 350

The Kawasaki Bighorn was my first real dirt bike. The link above tells you a lot about this history of this rotary-valved, 350cc two-stroke, 33-hp, 400+ lb. monster. It's important to remember, however, that these guys appear to like ancient motorcycles. What I remember most about my green machine was its unpredictability. The bike would do something different every time you applied the throttle, tried to turn, tried to stop, or tried to start it up in the morning. Occasionally, I felt like I knew what I was doing on this bike, when it went where I pointed it, as fast as I'd intended it to go. Usually, I felt like streamers dangling from the handlebars as the Big Horn rocketed into some obstacle that I'd intended to wheelie over, slid into a low-side because the motor busted the back wheel loose when I thought I had it loaded up enough to guarantee traction, or launched me into a high-side when the bike hooked up when I felt sure I could power through a turn steering with back wheel slip.

The Kawasaki Bighorn was my first real dirt bike. The link above tells you a lot about this history of this rotary-valved, 350cc two-stroke, 33-hp, 400+ lb. monster. It's important to remember, however, that these guys appear to like ancient motorcycles. What I remember most about my green machine was its unpredictability. The bike would do something different every time you applied the throttle, tried to turn, tried to stop, or tried to start it up in the morning. Occasionally, I felt like I knew what I was doing on this bike, when it went where I pointed it, as fast as I'd intended it to go. Usually, I felt like streamers dangling from the handlebars as the Big Horn rocketed into some obstacle that I'd intended to wheelie over, slid into a low-side because the motor busted the back wheel loose when I thought I had it loaded up enough to guarantee traction, or launched me into a high-side when the bike hooked up when I felt sure I could power through a turn steering with back wheel slip.I'm pretty sure the Bighorn weighed more than my 1992 850 TDM street bike. It sure handled worse, on or off road. But it did start me off on a lot of years of fun and adventure. And it was a pretty cheap bike to get started on ($300 for a like-new 1971 F5 in 1972). Since I fell down and broke bits of it almost every time I went riding, it was helpful that parts were cheap, too..

The one and only competition I ever attempted with the Bighorn was the Canadian River (Texas) Cross Country Race, in (I think) 1972). I was one of four open class bikes to finish the race, about 30 started as I remember. Because so few finished, the promoter only trophied to third class. All of the other classes trophied to fifth. It was one of the few times I had a chance to leave a race with something more than bruises and stories to tell and I'm still pissed about missing out on that piece of chrome plated plastic. Later, I managed to earn a few ribbons and some tires or accessory parts racing motocross and such, but that race was the last event I rode that actually offered a trophy and the last time I was in a position to earn one.

I moved the Big Horn with me from Texas to Nebraska, but quickly ended up on a Rickman 125 ISDT and the Big Horn ended up in a neighborhood kid's garage after the kid pulled the air filter in a misdirected attempt to "get more power." He got a burst of power, just before the leaned out mixture seized the piston and never managed to find enough money to put it back together. When I moved, the bike was being chewed up by garage mice and I doubt that it ever ran again.

Dec 5, 2016

Bikes I've Owned and Loved (a lot or a little): 1963 Harley Davidson 250 Sprint

T

My brother bought this bike somewhere around 1968. Being the abusive big brother I was, I used the heck out of the bike, mostly, against Larry's wishes and knowledge. He has been trying to catch up with me, on the abuse and creepy-ness scale, ever since. Since he's a terminally nice guy, I'm destined to stay in the lead for the rest of our lives.

The only good thing I can say about the bike is that it had two wheels and made more noise and was slightly faster than a bicycle with playing cards in the spokes. Kansas was an awful place to ride motorcycles in the 1960's. Folks you'd never met would go out of their way to run you off of the road. I became an "off road rider" because the ditches were where I spent all of my time, anyway. I figured that staying there was safer and faster than zigzagging from the road to the ditch every time a car passed me in either direction.