When I was young, still “made out of rubber and magic,” and full of unfounded confidence in my invulnerability I restarted my motorcycling life with a purchase of a 1971 Kawasaki 350 Big Horn. Motorcycles had been a big, then a small, then a non-existent, and back to big part of my life from when I was 15 until a year before my first kid was born in 1971. I didn’t buy the Big Horn new. It had belonged to an old Texas rancher who imagined that he could easily step down from horses to a motorcycle and discovered that he’d be relegated to a pickup instead. Today, I can relate to his dilemma, but back then I just saw his age-related misfortune as an opportunity. I paid a fraction of new price for a barely used bike and immediately went back to my old off-roading habits.

In those days, Hereford, Texas was a slightly prosperous west Texas ranching and cattle-feeding town with a side order of sugar beets and cotton. Today, it is practically a ghost town. Then, we had Honda, Suzuki, Kawasaki, and Eurotrash dealers, a hill climbing area, a barely-out-of-town motocross track, and hundreds of miles of poorly maintained farm-to-market roads that, often, were barely more than tractor tracks leading as far away as a rider would want to travel on an off-road motorcycle of the day. One of the guys I worked with, a welder named “Charlie,” was a local “bad influence” motocross phenom who rode a 250 Kawasaki piston-port motocrosser and who had found the Big Horn for me. He and I spent a fair number of evenings and weekends banging tanks at the Hereford track and flipping over backwards showing off at the hill climb area. It was all his fault that I almost missed the birth of my daughter, Holly, because he’d signed us both up for a Sunday race in Dalhart the weekend she decided to venture into the world.

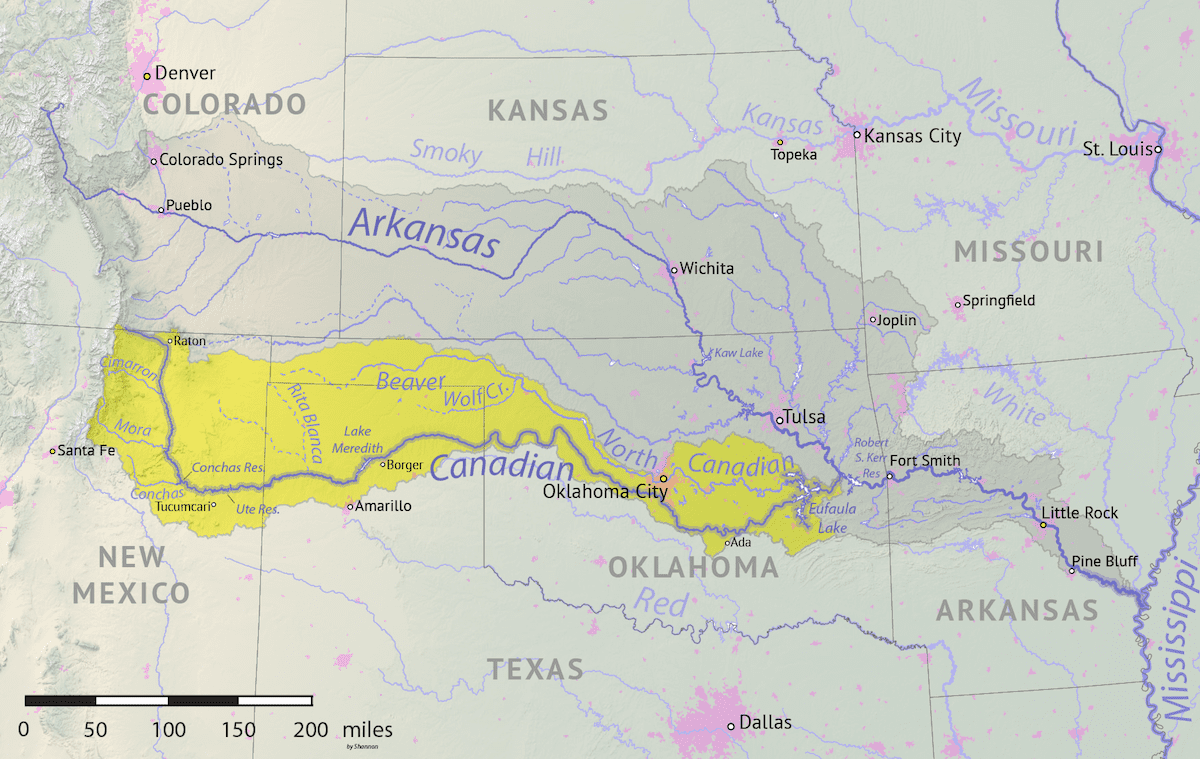

Since becoming a father ruined that weekend’s escape, A few weeks late, I signed the two of us up for the end-of-season race, the Canadian River Cross-country. A 120 mile race that started on the west end of Lake Meredith, a pitiful hole that might have been a lake at some time, but was just a big ditch most of the year in the 70s. From there west to New Mexico, the Canadian “River” was a long, wide trench with spotty pools of water, usually surrounded by rocks. I do not remember where exactly the race ended. 1971 was a LONG time ago. I remember my wife was really pissed that, after working a 90 hour week, leaving her home alone with a new baby, I was going to escape all of that bliss for a day and “go racing.” I was probably the least excited-to-be-a-young-father guy on the planet at that moment and her arguments were absolutely valid but unconvincing. Charlie was coming because he had a pickup and a great tool kit, but his interest in Cross-country was so slight that, after the first section, he turned back, loaded up his bike, and drove to the end to wait for me to show up so he could go home and get back to motocross.

Since becoming a father ruined that weekend’s escape, A few weeks late, I signed the two of us up for the end-of-season race, the Canadian River Cross-country. A 120 mile race that started on the west end of Lake Meredith, a pitiful hole that might have been a lake at some time, but was just a big ditch most of the year in the 70s. From there west to New Mexico, the Canadian “River” was a long, wide trench with spotty pools of water, usually surrounded by rocks. I do not remember where exactly the race ended. 1971 was a LONG time ago. I remember my wife was really pissed that, after working a 90 hour week, leaving her home alone with a new baby, I was going to escape all of that bliss for a day and “go racing.” I was probably the least excited-to-be-a-young-father guy on the planet at that moment and her arguments were absolutely valid but unconvincing. Charlie was coming because he had a pickup and a great tool kit, but his interest in Cross-country was so slight that, after the first section, he turned back, loaded up his bike, and drove to the end to wait for me to show up so he could go home and get back to motocross.

I was “determined.” When I lined up with the other open class bikes, maybe 20 of us, it was the first race I’d been in since my rough scramble days on the Harley 250 Sprint. The juices were flowing, I thought i was ready to race and, even, win, and my Big Horn was faster than snot. Heavy as a buffalo, but really powerful for the time. In recent years, I’ve been told that my motorcycles are “unfit for off-road purposes,” and I just laugh at that idea because most of those characters wouldn’t even consider a mess like the Canadian River Cross-Country on a 2022 enduro. My Big Horn was heavy (400+ pounds), barely-suspended with Boge shocks (maybe 3 1/2” of travel) and the stock forks, only made real power (33hp) when the motor was wound up past 4,000 RPM, and ungainly as hell. Every bike I’ve owned from my 125 ISDT to my XT350 to my TDM850 or V-Strom adventure bikes have been far more off-road capable than that Kawasaki so-called “enduro.” In late-1971, I had no idea that there were much better options and if I had been it wouldn’t have mattered because they weren’t available or affordable in West Texas.

The flag fell and off we went. I’d spent some time boning up on the warning flags and less than 10 miles in that education paid off. Just before we entered a tight, blind, hard left in the riverbed, one of those flags fluttered just enough to clue me in that there was a hazard. The hazard turned out to be a substantial pile of rocks that was littered with bikes, bike parts, and riders. I managed to come to a stop before piling into the guy who was in front of me. He didn’t. I paddled through a narrow passage and climb to the other side of the rocks and kept going. From here out, my memories are really clouded.

I know I crashed at least a dozen times in the next 100-some miles. I remember seeing a fair number of bikes and riders stuck in swampy sand, piled into rocks, logs, and each other. I remember, somewhere near the end, smacking my engine case on some rocks, busting the cases, and slowly losing the transmission fluid over the remaining miles. I remember only being able to shift from 1st to 2nd with no neutral or other gears in the last few miles. I remember losing power like crazy and barely motoring past the finish line. Charlie was there waiting for me and we loaded my bike back into his pickup. I remember drinking something, probably beer, on Charlie’s tailgate waiting for the results. I definitely remember a long period of no motorcycle, lots of overtime, and recriminations from my wife, while I reassembled and repaired the damage to my bike from that race.

My big memory, biggest in fact, of that race was discovering that because “only” three open class bikes finished, the organizers decided that they would only trophy to 2nd place, instead of 4th as planned and announced. I guess they wanted to save money on their crappy $5 plastic trophies. I got a fuckin’ ribbon, instead, but my finishing position wasn’t even listed, since I didn’t trophy. I raced motorcycles for another ten years, ending with a series of busted ribs, toes, and fingers. I never again came close to being on the podium. I pointed, in Nebraska, well enough to progress from Novice to Expert in the “Enduro Class,” but that was a quantity-over-quality achievement.

In the 1980s, when my daughter was skateboarding with her soon-to-be-famous boarding friends in Huntington Beach, she used to wear a tee-shirt that said, “I wish I were as fast as my father remembers he was.” I guess that is about as close as I will ever get to a motorcycle trophy.