All Rights Reserved © "Never argue with a fool; onlookers may not be able to tell the difference."

- Mark Twain I check the comments on this blog regularly. The idea is that we're going to have a conversation about the ideas I've presented. You should be aware of the fact that when someone emails me an interesting comment, the odds are good that I'll post that in the comments anonymously and reply to that comment on the blog rather than in email.

Sep 29, 2015

Deja Vu All Over Again

Sep 28, 2015

My Motorcycles: 1963 Harley Davidson 250 Sprint

My brother bought this bike somewhere around 1968. Being the abusive big brother I was, I used the heck out of the bike, mostly, against Larry's wishes and knowledge. He has been trying to catch up with me, on the abuse and creepy-ness scale, ever since. Since he's a terminally nice guy, I'm destined to stay in the lead for the rest of our lives.

This was, simply, an awful motorcycle. Like most Harley's, the Aermacchi/Harley was poorly engineered, under-powered, overweight, and unreliable. I bashed it a good bit of the way to death on figure-eight "rough scrambles" tracks in Dodge City, Kansas, but it wasn't worth much before I stumbled into it. The suspension was awful, so we replaced it with a pair of chunks of steel plate in the rear and shimmed the springs to immobility in the front. The footpegs kept breaking off, whenever I rode over any kind of bump. I learned how to weld in the process of reinstalling them every week or so. The motor started life weak and ended up so anemic that you could kick start it by hand.

The only good thing I can say about the bike is that it had two wheels and made more noise and was slightly faster than a bicycle with playing cards in the spokes. Kansas was an awful place to ride motorcycles in the 1960's. Folks you'd never met would go out of their way to run you off of the road. I became an "off road rider" because the ditches were where I spent all of my time, anyway. I figured that staying there was safer and faster than zigzagging from the road to the ditch every time a car passed me in either direction.

Sep 21, 2015

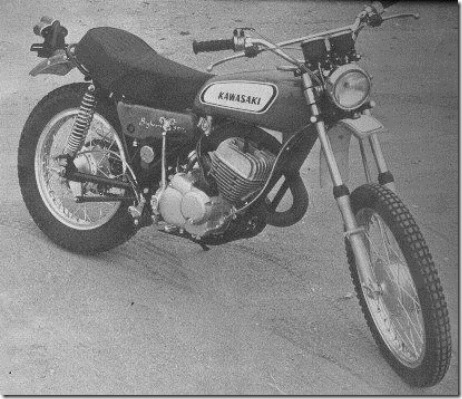

My Motorcycles: 1971 Kawasaki Bighorn 350

I'm pretty sure the Bighorn weighed more than my 1992 850 TDM street bike. It sure handled worse, on or off road. But it did start me off on a lot of years of fun and adventure. And it was a pretty cheap bike to get started on ($300 for a like-new 1971 F5 in 1972). Since I fell down and broke bits of it almost every time I went riding, it was helpful that parts were cheap, too..

The one and only competition I ever attempted with the Bighorn was the Canadian River (Texas) Cross Country Race, in (I think) 1972). I was one of four open class bikes to finish the race, about 30 started as I remember. Because so few finished, the promoter only trophied to third class. All of the other classes trophied to fifth. It was one of the few times I had a chance to leave a race with something more than bruises and stories to tell and I'm still pissed about missing out on that piece of chrome plated plastic. Later, I managed to earn a few ribbons and some tires or accessory parts racing motocross and such, but that race was the last event I rode that actually offered a trophy and the last time I was in a position to earn one.

I moved the Big Horn with me from Texas to Nebraska, but quickly ended up on a Rickman 125 ISDT and the Big Horn ended up in a neighborhood kid's garage after the kid pulled the air filter in a misdirected attempt to "get more power." He got a burst of power, just before the leaned out mixture seized the piston and never managed to find enough money to put it back together. When I moved, the bike was being chewed up by garage mice and I doubt that it ever ran again.

Sep 16, 2015

“I Messed Up.”

Three words most casual riders are incapable of saying, “I messed up.” It’s always “she pulled out in front of me” or “there was gravel on the road” or “I had to lay ‘er down.” Read “Kick Ass, Ass Kicked—it’s not not fate, it’s focus” for a racer’s take on what causes most crashes. It’s us. Nobody but us.

Sep 14, 2015

My Motorcycles: 1974 Rickman 125 ISDT

On one hand, it was a terrific motorcycle. The Rickman 125 ISDT (International Six Day Trials model) had strong, bulletproof motor and the bike was an artistic example of European design. The chrome-moly, nickel plated frame was an example of the finest workmanship. The quality and beauty of the welding was the best I've ever seen, anywhere.

While the radial head Zundapp motor was a nightmare of false neutrals and monster-Q powerband, the motor had a chrome-plated cylinder and rings. I think the Zundapp 125 would outlast any other motorcycle I've ever heard of, off-road. However, the powerband was so limited that it drove me to disassemble and reassemble the motor dozens of times, hoping to find some miracle that would put me in the front of the pack without having to spend hard-to-come-by money getting there.

In those days, I was earning $3.60 an hour and supporting a family of four on that wage. My average work week was 80 hours and I'd saved spare change for a whole year to scrape up the $500 to buy this bike. Regardless of how unsuited it was for the purpose I intended, it was going to have to work because I had no other choice. I raced the Rickman in the last few cross-country events in the Midwest. I thrashed it through several thousand miles of motocross tracks across Nebraska and northern Kansas, including "the big show"; the Herman, NE track where the nationals and international racers visited on the AMA and and TransAM tour. (My bike actually touched the same dirt as Roger DeCoster, Bob Hannah, and a host of great riders of whom you've probably never heard. I ground the Rickman's gears through a half-dozen enduros, a 24-hour winter endurance race in South Dakota, and, once, an observed trials. I even taught my wife how to ride a motorcycle on the Rickman.

Toward the end of my racing "career," all of the major damage I did to myself happened on the Rickman. More accurately, those things happened as I was being flung from the Rickman. Broken toes, fingers, ribs, collarbone, and all sorts of burns and road rashes. After 10 years of riding damage-free, I went through a six month period where I couldn't seem to keep the rubber-side down. At age 31, I quit racing while I could still stand mostly erect.

The left picture is of the Rickman in cross-country or enduro dress. Working (mostly) Bosch electrics, a Carl Shipman toolbag on the tank, and, otherwise, the same bike I raced on Nebraska motocross tracks. I'd gear the bike down about 6 teeth (rear sprocket) for motocross, because the top speed was 75mph over broken ground in stock form. The bike was so stable that a good (and light, less than 150 lbs.) rider could wick it up and hang on for miles, WFO.

The last cross-country race I did on the Rickman was in far western Sidney, Nebraska, about 30 miles from the Colorado border. I was blasting the 125 class when the race was called for the mother of all dust storms after the third lap. I looked like a filthy raccoon, when I pulled off my goggles and helmet and my eyes were so sandblasted that I could hardly open them the next day. The dust was so dense that it chewed through the master cylinder on my Mazda's hydraulic clutch on the way back home. We drove almost 400 miles, clutch-less, 100 of that through dust so thick that visibility was barely beyond the nose of our 1973 Mazda RX3 station wagon. The Rickman, however, was doing fine when the race ended.

It took a lazy Nebraskan, who thought air filters were for girly-men, to kill the Rickman. He put in a whole day of riding on the Platte River bed before the power vanished and he walked back home, leaving the Rickman to sink into the sandy river bottom. He even had the gall to call me and complain about the bike, two years after he bought it and 2,000 miles after I'd sold it to him. The bike's frame was a work of welding art. It should have enjoyed a much more honorable demise, but dirt bikes don't often die happily or attractively.

Sep 8, 2015

#121 It's Big or Nothing

All Rights Reserved © 2012 Thomas W. Day

My two days on the Yamaha Super Ténéré were eye-opening. There is an incredible amount of technology in that bike, just like the list of technology inside Yamaha's R1/R6/FZ1/FZ6 bikes or Honda's VFR1200F or Kawasaki's ZX-14R or Suzuki's Hayabusa or Ducati's anything or BMW's top-line sportbikes. The downside is that I can not imagine myself needing any of those motorcycles for what I do with a motorcycle. I ride to work. I take one or two trips a summer to semi-remote places. I saddle up and do day trips on paved and unpaved public roads, trail ride, or single-track the boonies just for the fun of it. I do not race anyone, ever. I never need the capability of exceeding 90mph, ever. A motorcycle that can do 0-60mph in less than 3 seconds is interesting, but unnecessary. I can no more consider the price tag for one of these giant-killers (or Monsters) than I can afford an evening with a supermodel. Superbikes are for rich kids. I'm not rich or a kid.My problem with all of this cool technology (fly-by-wire throttle control, traction control, variable fuel mapping, ABS and more sophisticated braking schemes, and the rest of the amazing electronic packages that come on the really amazing motorcycles) is that it is expensive and always comes with a substantial miles-per-gallon penalty. Once a manufacturer has made the decision to build a product with every trick they have learned on the race track incorporated into one hip-beyond-belief motorcycle, they have painted themselves into a liter-and-above corner. For example, I'm guessing that keeping the Super Ten's features, but downsizing the engine to a more fuel-conservative 600cc's (or smaller), would result in a MSRP price reduction of less than $2,000. I can not imagine anyone except Ducati or BMW convincing their Kool-Aid drinkers to fork over twelve-grand for a 600cc-or-smaller motorcycle. It has to be a non-starter for Yamaha, as perfect as that motorcycle would be for the 21st century.

Imagine a 60+ mpg motorcycle with comfortable and flexible ergonomics, ABS and linked braking, variable fuel mapping, traction control, and practical long distance touring features. The closest thing we have to that motorcycle is Suzuki's V-Strom 650 ABS, which has about 2/3 of the Ténéré's electronic and mechanical features (no fly-by-wire traction control, no selectable fuel-delivery mapping, no "unified" braking, non-cartridge fully-adjustable forks, and a substantially less adjustable shock). It's also about 60% of the Ténéré's list price, at $8,300 MSRP. It would be reasonable to assume that adding all of those features might get the V-Strom's price near the Super Ten's without even changing the motor size. In fact, the V-Strom 1000's price is $10,400 without ABS and with basic FI.

What I suspect this all means is that the choices are limited to "go mid-tech and small" (like the Honda CBR250R, Suzuiki TU250X, or .Yamaha's WR250R) or "go big and get it all." With entry level bike prices climbing into decent used car territories, the resistance to offering a rational-sized high-tech motorcycle is probably a good short-term tactic. Motorcycle company marketing departments have demonstrated little-to-no ability to drive the market and, therefore, all of the big companies are just selling "me too" products in the US. This is would be a place where taking a page from Apple's playbook could produce some big returns for the first player into this untapped market. Suzuki has maintained a tight grip on a good bit of the mid-sized (650 twin) sportbike and adventure touring business with Kawasaki and Honda bringing the Versys 650 and NC700X DCT both late to the market and long after Suzuki satisfied a a lot of the buyer pipeline. Only the Honda offers ABS and neither bike really qualifies as equivalent competition for the new V-Strom or comes close to the Super Ten's technology.

You'd think this would be a hot market in a high-price fuel, newly functionally oriented market. The big cruiser market is aging and dying. The low efficiency sportbike business has limited appeal from a comfort, practicality, and sensibility perspective. Standards and adventure touring bikes may be the future of motorcycling and the industry seems to be ignoring this customer base until somebody else cracks the barriers. Suzuki proved that the first one into the pool wins. So, who's going to be first to import a high-tech, sub-700cc all-around motorcycle?

Sep 1, 2015

Motorcycle Reviews and Me

I’ve bitched about product reviews from several industries, including motorcycles, for almost two decades. Now that 99% of magazines count on advertising revenues rather than subscriptions for their income, editors/writers are more worried about pissing off an advertiser than providing value to readers. One of the things that first attracted me to writing for MMM were the reviews I read in those late 90’s editions. Far from soft and fluffy, some of the reviewed bikes took a beating. My benchmark product magazine is and always will be the version of Dirt Bike Magazine the ultimate geezer (even when he was a kid) Rick Sieman (SuperHunky) edited. He’s still at it, a bit, with articles like “Worst Dirt Bikes of All Time” and better. For the rest of the written world, readers don’t amount to much in terms of attempts at value provided. In fact, we’re not really “readers” in modern magazine vocabulary, we’re “customers.” Just like the MSM when talking about American citizens, we’ve lost our citizenship and become “consumers.” For my money, if the printed word disappears from existence it won’t be missed if I never again find myself referred to as a consumer or customer.

Here’s my real complaint about this kind of review, though. As I wrote to Sev, “Comparing the 750 to other Hardlys makes the bike look . . . better. It might have been useful (to new riders) to mention that the "more powerful" Hardly 750 makes 10hp less than, say, the V-Strom 650 and about the same torque and includes ABS for similar money.” His response was, “One cannot rail on H-D for doing the same-old same-old then curse them when they produce something (gasp) modern.” I can and will. While finally realizing that air cooling and carbs are for lawn tractors and museums is a nod toward “modern,” it’s a long, long way from 2015 technology and getting further every day.

It’s true that everyone’s cruiser offerings are pretty primitive, but review after review calls these “small” hippobikes “starter bikes.” Would you put your kid on a 60 pound, coaster brake, single-speed, 26” Schwinn cruiser as a starter bicycle? Yeah, I know that’s what I started on and it’s a pure miracle I’m alive to talk about it. I crashed that POS bicycle into mailboxes, fire hydrants, buildings, and cars before I began to realize my father didn’t know shit about picking a bicycle for a kid. Apparently, the whole motorcycle publishing industry got it’s cue from my father: a high school business teacher who was baffled by a newspaper wrapping machine to the point that he’d hand-rubber-band 1,000 newspapers rather than try to unclog a string jam.