Warning: This story is only as accurate as the author's memory.

I have done a lot of moderately risky things in my life, but I will aways put bowling at the top of the list of scary, risky, painful, dangerous things that I will never do again. This is an old story and I’m sort of amazed that I haven’t told it before, but I did a thorough search of this and the Wordpress blog and didn’t find a single word about it. So, in the late stages of my life and whatever is left of my two-wheel “career,” I am going to explain my terror of all things related to bowling.

It all started when I was just a kid. My father was a pretty decent adult athlete, although I guess he wasn’t much as a kid. Into his late 60s, he played competitive tennis at the Kansas state championship level, bowled consistently in the 230-250 pins territory, had a decent golf handicap, and when he was in his 40s he played basketball well enough to be recruited for the Washington Generals when the Harlem Globetrotters were in town. He was also a high school basketball, football, and tennis coach until he was well into his 60s. From about 5-years-old on a good bit of my life revolved around sports. Usually, thanks to asthma and other physical limitations, sports that I didn’t play particularly well. I never managed to play any of my father’s favorite games well enough to impress him and a couple of them—golf and bowling—were sources of irritation for both of us. Still are. Much later in life, I had a spurt of playing beach basketball in California, but that was a world and a game totally outside of his experience.

Moving forward about a decade and I’m a twenty-something working-class husband and a father of two beautiful daughters, I worked a lot of 80-hour weeks, drove a worn-out 1969 Ford E100 panel van 100,000 miles a year across six Midwestern states without A/C or heat. I was employed by a con artist of a boss who generated a lot of angry and disappointed customers. My only escape from pressure, stress, and confusion was the occasional few hours I was able to spend on my dirt bike.

After a couple of years in small town Nebraska, Mrs. Day, on the other hand, was getting desperate for a social life outside of caring for our two little girls and visiting with other mothers of small children. So, she signed us up for a bowling league, partnering with the only young couple she knew who didn’t have kids. I managed to slither out of the first two league games, claiming (honestly) that I had to work at the other end of the state those evenings. The third match was unavoidable. I couldn’t get out of it because my slimeball boss caved in to my wife’s complaints about her missing-in-action husband and “gave” me the weekend off.

Other than rolling a couple of games with my father and brother during the occasional holiday break visiting my family in Kansas, I had managed to stay away from bowling alleys for a long time. By that point in my life, I had learned that “games of patience” do not play to my strengths. Anything that requires me to do the “zen focus” bullshit when I’m losing is only going to be frustrating. I played and loved basketball well into my 50s because catching up (or staying ahead) requires working harder. Same for racing motorcycles, to catch up or stay ahead you work harder and go faster. Golf and bowling require the player to concentrate on form and geometry and I suck at both. So, that evening at the bowling alley started poorly, with me tossing a couple of gutter balls and barely grazing the end pins in my first couple of frames. Mrs. Day wasn’t much better, but she wasn’t expected to be and our new friends were getting cranky only a few minutes into the evening, which promised to be long, boring, and pointless.

I am an alcohol-lightweight. I have been drunk twice in my life and neither of those episodes had yet occurred. I can easily nurse a portion of a beer or a mixed drink for several boring hours at a party and one drink is usually my limit. About two beers into the bowling evening and I was losing interest in the game and I decided to redefine the fundamentals of bowling. Just rolling the ball down the lane was an insufficient challenge and I started trying to see how far I could heave the ball before it struck wood. I wasn’t going for altitude, just distance, but the ball began to make a fair amount of noise when it landed after I’d suffered through the first game of the three we’d committed to playing. About the time I started to think I was getting the hang of this version of bowling, probably at about the 3-4 beer mark, the bowling alley proprietor asked me to leave. Mrs. Day and her friends were embarrassed. Our new social life came to a screeching end and I don’t think I ever saw the other couple again. In fact. I don’t remember being at all upset at being done with my moment in small town social life.

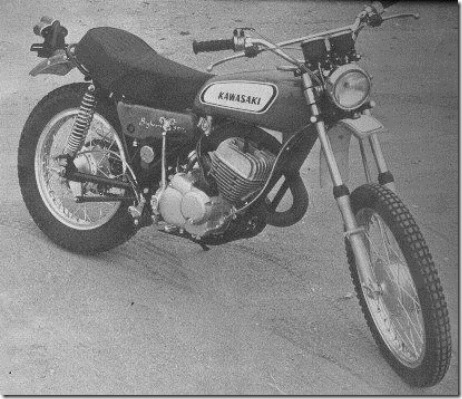

After the bowling debacle, I still had a weekend off. I had planned the next day, Saturday, for some recreational practice time on the limited-access roads I loved about 20 miles north of our home. I’d loaded up the Rickman the previous evening, strapped a couple of five-gallon cans of premix to the trailer, loaded my privative 1975-style gear into the family station wagon, and headed north for some trail therapy. Sunday was race day and I’d signed up for my usual spot at the back end of the Nebraska State Intermediate class races. And I’d be wrenching for a friend who was actually competitive in the Expert class.As you might suspect, I was slightly hungover that morning. Having never been even a little hungover, I was clueless as to what that might mean. The place where I chose to make my stand was in the sandhills about five miles east of Palmer, Nebraska and about the same distance south of the Loup River. Back then, this area had well over 100 miles of limited-access roads tied together in a way that allowed me to ride for hours without ever crossing pavement. And that was my plan for the morning. My excuse for running out on my family on a beautiful Saturday summer morning was that I would be “practicing for Sunday” at the races in Genoa. That was sorta true, but mostly I was getting as much alone-time as possible anyway possible. But I was unwittingly impaired.

I unloaded the bike from the trailer, strapped on my gear, gassed up the bike, and took off heading north toward the Loup River. The first section of the route I’d planned was over some mild hills thoroughly coated with deep, fine dust bowl blow-out sand. I don’t know if I have ever ridden a motorcycle more suited to that kind of riding. The Rickman didn’t have much low-end torque, but once you spun it up over about 4,000 rpm it would sail across the sandhills like a prairie racing catamaran.I had barely got the bike warmed up, less than a few miles from where I’d parked, when I let the bike slide down the side of a sandhill into a tractor rut. Normally, no big deal. Just haul back on the bars, give it some throttle, and sail back up the side of the hill. Hungover, I considered a brand new option: step off of the bike and bail out. I was doing about 50mph at the time and abandoning ship was a freakin’ stupid option. I discovered that immediately. The thing about the next few seconds that has stuck with me for 40 years was a sound I can only describe as “a pound of hamburger thrown hard against a refrigerator door.” Splat!

Some undetermined, but calculatable, period of time later, I awoke imbedded about a foot into soft, hot sand. While I was unconscious, I’d hallucinated that I’d been tossed out of an airplane without a parachute. When I woke up, the dent in the sand, the pain, and the near-desert surroundings fit nicely with that hallucination.With some effort, the time I’d been unconscious could be mathematically be determined by the flow rate of fuel from my Rickman’s tank overflow hose. When I righted the bike, I discovered I needed to change the petcock to reserve to get the engine started. My guess was that I’d been unconscious for at least 20 minutes. Getting the bike upright was a challenge, I hurt everywhere, but mostly I couldn’t catch my breath. Getting turned around in that deep sand was another challenge. Getting the bike started and moving in the right direction was tough, but easier than the first two hurdles. By the time I made it back to the parking spot, I was having serious problems breathing. I absolutely failed to lift the Rickman’s actual 250+ pounds (216 pounds claimed weight![]() ) on to the trailer. In frustration, I climbed into the station wagon, reclined the seat, and decided to see if I might feel better after some rest. After a few minutes, I was so seized up and hurting that I couldn’t get back out of the reclined seat. And breathing was harder, not easier.

) on to the trailer. In frustration, I climbed into the station wagon, reclined the seat, and decided to see if I might feel better after some rest. After a few minutes, I was so seized up and hurting that I couldn’t get back out of the reclined seat. And breathing was harder, not easier.

Sometimes the old adage, “No good deed goes unpunished,” gets proved wrong in spades. Over the past year, I’d put a lot of effort into being friendly and useful to the area’s ranchers. I had helped chase cattle back through downed fences, ridden to the nearest ranch to tell the owners about damaged fences or escape cattle, and always stopped to talk (rather than run away like other dirt bikers usually did) when I met someone working the fence lines bordering the limited-access roads.

As I lay in the car imagining what the odds anyone would find me out on this remote road before I suffocated or starved to death, three actual cowboys rode up (on actual horses) and stopped to talk. I was barely able to say “howdy” and real conversation was beyond my capacity. After a bit, they figured out my predicament, pulled me from the vehicle, loaded up the bike and strapped it down, helped me pull off my boots and gear, turned the car around, and even offered to drive me back home if I couldn’t manage it. [That wasn’t the first or last time I’d be rescued by cowboys or horses.]

Because I was, and probably still am, an arrogant, macho/dumb male, I declined the designated driver offer, gritted my teeth, engaged the clutch, shifted into 2nd (to minimize having to repeat that painful movement), and took off for home. I had to pass through two small towns and about half of our hometown on my way home and braking or shifting quickly identified themselves as painful and impossible tasks. For the first and only time in my life, I desperately hoped a cop would stop me and arrest me, even shoot me and put me out of my misery. But I sailed through both towns and the north end of our hometown at 60mph without a glitch. I think I even blew through two stop signs on the way. The station wagon was a 1973 Mazda RX3 and it would easily do 60 in 2nd gear and start with a little clutch slippage, so I didn’t shift all the way home.

I pulled into our driveway, turned off the key and shuttered to a stop, but I couldn’t get myself out of the car. I blasted the horn until Mrs. Day and our little girls came out to see who and what was causing the racket. They helped me out of the vehicle, into the house, and on to the family room couch. After a bit, I thought a hot bath might help, so I went into our bathroom and ran a tub-full of near-boiling water. And I almost drowned when I discovered I couldn’t keep from sliding into the big old clawfoot tub and going down helplessly. I slept on the couch for the next few weeks because our bedroom was on the impossibly-distant second floor.

When I finally made it to the local doc’s office, an x-ray determined that all 12 of my left-side ribs were broken or cracked. The closest thing to sympathy or assistance I got from my doc was, “That’s what you get for riding a motorcycle.” The injuries put me out of work for more than a month and, thanks to the usual 1970’s small business total lack of any sort of disability or healthcare benefits, about destroyed our family’s economy, . However, I had more than enough vacation time, so at least I got paid for a 40-hour week while I was out of work. A few weeks after I was back to work, I ran into the doc limping around our grocery store, on crutches with his leg in a cast. I sympathized with him by saying, “That’s what you get for playing with those damn skis.”

The long-term effect of the crash, the pain, and the extended recovery time was that for years afterwards when I got into any kind of extreme situation on a motorcycle (a little air, going a bit sideways, skittering along a sandy section of road or track) I PTSD’d myself into going through the worst part of that desert crash and usually found myself parked on the edge of the trail or track sweating and panicking over another crash that had only happened in my mind. It was several years before I could really enjoy offroad riding at any sort of respectable speed and look what that got me.