[For the last many years, I’ve said Geezer #1 "What Are We Riding For? (The original, from whence The Geezer came from October 1999" was the first thing I ever wrote for Minnesota Motorcycle Monthly magazine. I wasn’t lying, I was just wrong. I have been working on a Wikipedia entry for the magazine and as part of that I researched as much as I could find about the magazine’s history. In the process, I read through a bunch of old MMMs, sorted my own collection by date, and discovered that in the Winter 1997 M.M.M. #14 issue there was an “On the Road” article. . . by me. This article, in fact. While I absolutely remember the trip, sort of, I absolutely did not remember even knowing about MMM before 1999. Turns out, that was wrong, too. In September 1998, I contributed “Look Ma, No Feet!” an article about the 1998 US Observed Trials event in Duluth. So, now the story I’ve been telling myself and everyone else about my history with MMM is bullshit and I do NOT know what the truth is.

The version that follows is what I submitted. Unlike lots of the stuff I wrote for MMM, this article was edited quite a bit, but I’m too lazy to pick out what was different in the magazine’s version.]

Every year, since I moved out of Colorado, my expedition to the Steamboat Springs Vintage Motorcycle Week gets a little tougher. Last year, I flew to Denver, borrowed a friend’s Honda Hawk, and nearly missed my flight home when my luggage fell off of the Hawk in the middle of traffic on I-70, spreading my belongings and plane ticket all over Colorado. This year, I decided to ride the whole 2,400 miles. Next year, I may try walking.

My bike is a ’92 Yamaha TDM, which is a weird cross between a crotch rocket and a dirt bike. It’s probably the closest thing Japan will ever come to importing a Paris-Dakar style bike to the US. Out of some weird allegiance to my dirt biking past, I put dual-purpose tires on the bike this past winter. Because of that strange heritage and hardware, I actually hoped to do some real cross-country touring this trip. Some people do not get wiser as they get older.

Because I had a few days of vacation to burn up, I left for Denver early Sunday morning, September 7th. Steamboat’s Vintage Motorcycle Week was September 10 to the 14th. The start of my planned route was diagonally across Minnesota, via highways 169 and 60, to Sioux City. Early in the day I passed the Mennonite settlement of Mountain Lake, MN, where there is a "phone museum" and other exciting attractions. I’d always thought of Mennonites as hardworking, honest types, but this place had to be their equivalent of a Florida swamp real estate scam. There is no no mountain and no lake, as far as I could see, anywhere near Mountain Lake. I have a new sort of respect for Mennonites.

I stopped in Heron Lake for my first fuel stop. I discovered, by drenching my bike and feet in gas, that the fuel shutoff was defective. With the helmet and ear plugs in place, I nearly dumped two gallons of gas on the ground before I noticed I was creating a Super Fund site. From here out, I did my trip documentation after filling the tank. It didn’t surprise the lady at the counter though. She said, "that side don’t register, this side does," when I told her about the screwed up pump. I kept an eye on the mirror, as I left town, half hoping for a mushroom cloud to compensate me for the wasted fuel.

Just south of Worthington, I tailed a yuppie in a Range Rover who showed no fear of Iowa’s CHP. He got me through that mind-numbing state in record time. I stopped at an interstate rest stop in Iowa where an old lady with a highway department uniform told me "I used to be in the bidnez worl’, that’s why I’m workin’ here." I thought she meant the business world ruined her life, but she was just working for the exercise. Go figure. Just south of Sioux City, I hooked up to highway 77 and to some even less regularly maintained roads.

I used to live in north eastern Nebraska and I mistakenly thought that gave me some ability to pick my way across the state. I ended up on a newly graveled road, about 10 miles north of North Bend, that was terminated by a large crane and a missing section of road. When I stopped to look at the construction damage, my wheels sunk past the rims. My next short cut took me though about 5 miles of really deep gravel and sand. By the time I escaped that desert riding experience, my front fender had a 3" hole pecked into the back side and my chain picked up about an inch of slack.

After relocating asphalt, I picked up 30 at North Bend and headed west. I failed the "will to live" test and stopped for a hamburger in Columbus, NE (Actually, I figured that ought to be the safest place in the US for a beef-eater, after that city’s most recent 15 minutes of fame.) Making up for lost time, I stuck with 30 to Grand Island and jumped to I-80. By the time I got to Gothenburg, NE; 630 miles from home, I was wiped out. I stayed in a truckers’ motel that night and set the alarm for a 5:00AM takeoff.

Poor road maintenance almost bit me in the butt this morning. I had a low rear tire and thought I’d developed an oil leak when I stopped in Julesburg, CO. The tire was low, but OK. I washed the engine and discovered the oil leak was just chain lube that was heating up and dripping off of the engine cases. I promised my self I would watch my oil level and temp gauge carefully for the rest of that leg of the trip, just in case. I managed to hold to that promise all the way to Denver, about 120 miles. Later in the trip, my failure to extend this pledge to the whole journey would haunt me.

By noon Monday, 372 miles later, I was in Denver. You can’t see the mountains until you are about 55 miles from the city. Mountain cloud cover suddenly becomes mountains and the air seems cooler and fresher. The last 50 miles into Denver seem to go quickly and the horizon’s view is terrific.

When I stopped, my butt hurt. My kidneys were falling out in chunks. My bike needed about 10 hours of serious maintenance. Being the high tech, serious maintenance guy I am, I lubed and re-tensioned the chain, put duct tape over the hole in the fender, washed the bike, checked for loose hardware, washed my laundry, and hung out in a bar until Wednesday morning.

Six of us left my friend’s home for Steamboat Wednesday at about 8:30AM. We were probably the weirdest collection of motorcycles on the highway that morning: a Yamaha TDM (mine), two Honda new Magnas, a ’78 Kawasaki Scepter, and an ’83 Yamaha Venture. After a few miles, we strung out across the highway in a several mile long "touring pattern."

We intended to get to Steamboat by noon so we could catch a little of the dirt track speedway racing in Hayden that afternoon. We’ve made that plan five years in a row. Like the other years, this year we didn’t get to Steamboat until 1:30PM, our trip schedule was sabotaged by several coffee, fuel, and meal beaks. Some of the group, including me, thought the lodge’s hot tub looked more interesting than another 100 miles on the bikes. Those who stayed watched the clouds cruise the mountain tops and drank beer. Those who left got to Hayden just as the last of the racers were leaving and got caught in a short rain storm on the way back. I try to make each of my millions of mistakes only once.

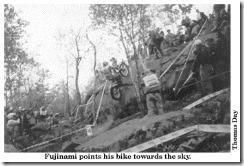

The next day, I went to town by myself because none of my group was all that hip on the trials event. This is the sport with which I ended my 15 year off-road competition career. In fact, the years defined as the end of "vintage" were state-of-the-art just before I quit trying to luck into a trophy. Every once in a while, Steamboat makes me reconsider my constant fear of knee injuries and I think about buying a Bultaco Sherpa T or a Yamaha TY and doing a little cherry-picking. Steamboat’s vintage traps are almost all easy enough that a good rider could zero out on a street bike.

This is also the day where the "geezers on Beemers" sub-title for Steamboat really becomes appropriate. There seem to be an incredible number of retired executives, military officers, and other non-working class types doing the vintage-bike gypsy tour. They live in 40’ luxury campers and tow bike-trailer/work-shops that make my garage look puny and unequipped. A few of them even have trophy wives in tow. Since most of these guys are pretty near my age and I don’t have any of that stuff, I try not to make too many comparisons or I’ll get discouraged.

I really get a kick out of seeing how many ancient bikes have been modified for trials. I didn’t even know BSA or Greeves made a 125 or that anyone was riding trials pre-WWII before my first trip to Steamboat. This is like a dirty, live-action museum with some dirty, active museum caretakers riding the exhibits. It rained a little about 10:00AM, just enough to send me back to the bike for my jacket. As soon as I had two arms full of stuff to carry, the weather got hot and I spent the rest of the morning sweating and grinding dirt into all of my body parts. I don’t know who won, probably some geezer with a collection of Beemers and a Yamaha TY in like-new condition.Friday is vintage motocross day. Another of my favorite events. Again, I was up and out before the rest of the group. I spent the early morning walking through the pits, taking pictures, listening to experts talk about the history of various, long-dead motorcycle manufacturers. It’s still hard for me to reconcile Rickman, Bultaco, Ossa, Norton, BSA, and the rest of the deceased as being not only dead, but long dead. Seeing these bikes back in their prime, sometimes much better than prime, is a lot of retrospective fun.

The actual races are almost anticlimactic. It’s always a kick watching Dick Mann win. He was a Baja hero of mine when I was a kid. He’s still heroic at sixty-something. Dave Lindeman, a Denver fireman, put on a good show in the Open Twin Expert class, dueling and beating Rick Doughty’s zillion dollar Rickman/BSA on a cobbled up Yamaha XL650.

But lots of the actual races are pretty boring. There are wads of timid, over-forty wannabes who barely turn their bikes on in the straights and come to a lethargic near-stop at every corner. The race to the first turn is often more humorous than exciting. Everyone is so concerned with avoiding contact and a crash-and-burn that they barely make it to the turn, let alone work for a decent position on the other side. In the bulk of the races, there is rarely more than two half-decent racers. The other two dozen geriatric cases are nothing more than track obstacles when the fast guys start lapping them. The upside, for me, is that I regularly get pumped about buying an Elsinore and stealing a trophy. The downside is after making a couple of deep knee squats, I remember why the majority of the riders are going so slow. Getting old is hell. The body can’t even remember how to do what the brain told it to do.

Fairly late in the afternoon, the races are over. We cruise the streets of Steamboat, looking at bikes we will never own. This really is a BMW convention. I doubt there is a bike BMW ever made that isn’t represented here. Seems like there are more Harleys this year, too. Maybe that’s why the local paper doesn’t have a single word about the events. In years past, I could read about what I’d seen the previous day in the local rag. Not this year. There must be several thousand bikers in town and the only mention of motorcycles was when a local biker got smacked by local cager. It’s not like this is a pack of Outlaws, tearing up the bars and defiling local women. A pair of women, climbing out of a Jeep Cherokee on their way to lunch, asked one of my buddies if we were a "biker gang." He told them, "Yeah, after our nap, we’re gonna take this town apart!" That’s about the speed of everyone at Steamboat. Sedate. Old. Mostly intent on finding a good restaurant and a decent hotel. I guess we still found a way to scare them.

I didn’t cruise much Friday night. We really did find a great place to stay and I headed back, well before dark, to sit in the hot tub and watch the clouds and the mountains flare and fade in a crimson tinted sundown lightshow. Beer, a good book, a hot tub, and tired, old aching joints really go well together. If a local female stripped herself and jumped into my hot tub, I might have defiled her but I’d have more likely been pissed that she got my book wet. I bought my beer at the Clark Store, so I didn’t even have a chance to think about trashing a bar. I’m a pretty poor excuse for a biker, I guess.

Saturday is vintage road racing and the first opportunity we have to look at the concourse. We buy pit passes, which are $20, and head for the pits. I’m not much of a connoisseur of street bikes. In fact, I never paid any attention to street bikes at all until I’d been riding and racing for almost 15 years. I still don’t really know one cruiser or crotch-rocket from another. I don’t much care about cars either. But there are some really neat, loud noises coming from the pits and one of my friends has a great time describing all the bikes to me. I lecture on the dirt bike days, he does the street day.

About two hours into Saturday, I got bored. This is a terrible thing for a "reporter" to admit, but I’d have rather been riding than watching. When I fell asleep and lost track of where the rest of my group had gone, I decided it was time for me to hit the road. I’d planned on leaving that day, anyway, and it seemed like the time to do it. I wandered around the course for another hour, trying to find everyone, with no luck. I stuck a note on a friend’s seat and started getting ready for the long ride back to Minnesota.

Sunday is the modern road race. I have been going to Steamboat for 6 years and I’ve never stayed for the modern road race. My justification for leaving early is that I can watch modern crotch rocketing any weekend during the summer and I never do. Why blow a good day of riding watching someone else have a good day of riding? Like all the years past, I left on Saturday and missed the really fast guys. They’d just discourage me, anyway.

The real reason I wanted to leave early was that I wanted the extra riding time so I could go back the long way, through Wyoming and South Dakota. I retraced my trip into Steamboat back over Rabbit Ears Pass. About 30 miles east of Steamboat, I turned north on Colorado 14. This is one of the prettiest roads I’ve traveled in Colorado. It’s a neat combination of mountain plains and ranch land. The road isn’t particularly twisty, but it does curve its way through a beautiful section of the Rockies. The road is well maintained and completely unoccupied by cage or cop. I made good time to Walden, where I picked up 127 and continued north to Laramie, WY.The scenery doesn’t stop when you leave Colorado. Good roads and great views all the way to Laramie, where I copped out and took the freeway (I80). After 300 miles of awesome two lanes, I80 was a complete bummer. But I stuck to it to Cheyenne, where I swapped freeways and took I25 north to Wheatland. I spent the night in Wheatland, at another truck stop. Leaving Steamboat early allowed me to knock off 250 unproductive (destination-wise) miles before I seriously head for home.

The actual route I took from Wheatland to Deadwood is up for discussion. I know I stayed on I25 for a few more miles to Wyoming 160. I know I swapped off of 160 to 270, because I had breakfast in Lusk, WY. I’m not sure I stuck with 270 all the way to Lusk, though. A good portion of that trip was on dirt roads. I mostly used the sun as a compass and tried to keep going north at every intersection. I popped out of the last section of dirt road on highway 85, just a few miles south of Lusk. I had been on reserve for about 30 miles when I filled up in Lusk. I’d like to tell you 270 to Lusk is a terrific road, well worth traveling, because it is. I’d like to tell you that I strongly recommend this route for the scenery and adventure, because I really enjoyed that aspect of the trip. The fact is, this is a route that requires a great suspension. The road (the real road, not the dirt road) is heavily traveled by farm equipment and is pretty rough. The TDM ate it up, but a crotch rocket or cruiser would deliver a severe pounding. You decide.

Leaving Lusk, I forgot to reinsert my ear plugs. Good thing. I heard several nasty noises and pulled over for a maintenance stop. You’ll probably notice that I haven’t mentioned maintenance since just before I pulled into Denver. I hadn’t done much since then. Another brain fart. The older you get, the more of them you’ll have. I discovered the front fender had a new hole, this one on the front, from poor tire-to-fender clearance and flung gravel. I pealed away pieces that were touching the tire and "fixed" that problem. I also discovered my chain was really wearing out fast, probably due to the off-road portions of the trip. It was actually hanging up at spots as they passed over the countershaft sprocket. I bought a can of WD40 and thoroughly cleaned the chain. I lubricated the chain and made some more promises to myself regarding maintenance.

The next section of the trip was sort of frightening, considering the condition of my bike. There is next to nothing between Lusk and Deadwood, 140 miles of nothing. There are some towns listed on the map, but they are barely bumps in the road. Some of them aren’t even that. But I took this route because I was bored with the trip across Nebraska and Iowa, so I figured it was worth continuing. Not that I had much of a choice.

Wyoming is a great state. I suppose every state has a motto. Nebraska blabs about some mystical "good life" that no visitor or resident has seen any sign of. Iowa yaks about "liberties" and "rights" and parks a cop on every road to make sure no one ever even dreams about freedom. Colorado’s "nothing without providence" is totally meaningless. But Wyoming is the "big country" and you don’t have to look far to find real cowboys just like the one on their license plate. Some of those cowboys drive farm trucks on highway 85. I only saw four vehicles on the road between Lusk and the South Dakota boarder. All of them were doing 90+ mph and they all waved when they went by me. I would have stayed with them, but I wanted to live through this section of the trip with chain intact. There is nothing, in any other part of this country, like the concept of "safe and reasonable" as a speed limit. It almost makes me feel like an American. Out there, Mamma Government is in short supply and nobody misses her.

The weather totally cooperated. From the beginning of this day until I hit the plains, just west of Wall, SD, the sky was clear, the temperature was in the low 70’s, and the wind was nonexistent. South Dakota’s Black Hills are a national treasure. South of Deadwood, 85 winds through the hills like the best Rocky Mountain highway. There are miles of twisty, narrow highway that parallels beautiful streams and cuts through wooded valleys and farm land. I could take a summer long vacation, traveling the roads of the Black Hills, and never grow even a little tired of it.

I made it to Deadwood in one piece. Stopped for gas, lubed the chain, washed the windshield, checked the tires, and thoroughly inspected the bike. Then I walked to the Deadwood Historical Society museum and wasted an hour looking at the coolest of western history. There are Harleys all over Deadwood. It’s only a few miles from Sturgis, which must account for all the heavy iron.

I still hadn’t eaten when I left Deadwood. I was making, and having, such good time that I couldn’t convince myself to waste any of the day in a restaurant. Slightly north of Deadwood, I struck interstate and there I stayed until Minnesota. Once you pass Wall, the home of Wall Drug, there isn’t much to say about South Dakota. Every diddly-butt town has some kind of tourist trap. None of them are worth stopping for. It’s not just that there’s nothing to see in those towns, there’s nothing to see in that part of South Dakota. It’s just miles and miles of flat, boring plains. Most of the state’s rest stops are "out of order," probably to force travelers to waste time and money in the state’s tourist traps. I stopped for gas at Wall, Chamberlain, and Sioux Falls. There isn’t much more to say about the space between any of those cities.

The wind was killer, once I passed Wall. It was 50+mph and I felt like I was making the world’s longest right turn. 420 miles of right turn. I wanted to make Sioux Falls by nightfall, but I was forced to take a stretch break every 50 miles. My arms, back, and butt were going numb and the road never seemed to end. I swear that some of the mileage signs increased the distance to Sioux Falls as I drove east.

The only break in the monotony comes a few miles before Chamberlain, SD. The Missouri River valley almost instantly changes the scenery. It takes you from flat, barren plains to green rolling hills in only a few miles. The river is awesome, especially after 200 miles of desolation. It’s as wide as a lake and as blue as an ocean. Unfortunately, 10 miles east of Chamberlain, I’m back in a windy desert. That evening, 650 miles from where I left that morning, I pulled into Sioux Falls and headed for a Super 8.

The next morning, I tried to sight-see in Sioux Falls but failed to find any interesting sights. I left town at about nine and headed for home. I repeated the original leg of the trip by exiting I90 at Worthington and take 60 to 169, through Mankato, and on to the Twin Cities.

I got home a little after noon. I popped the cap on a beer, filled up the hot tub, and fell asleep dreaming about high mountain passes, unlimited speed limits in Wyoming, and gorgeous snaky roads in the Black Hills. I woke up, sweating, later that night when the dream turned to wind blasted, straight and boring South Dakota interstate dotted with hundreds of Iowa Highway Patrol cars.