One Week

written and directed by Michael McGowen, 2008

All Rights Reserved © 2011 Thomas W. Day

This is one of the rare movies that will actually make you feel better for having spent the time; none of that bitter aftertaste of a wasted evening from One Week. The Internet Movie Database called One Week an "adventure, drama." Netflix (which currently has One Week on Instant Watch) categorizes the movie as "Indie Dramas, Romantic Dramas." I would have called it a dark comedy. It is, honestly, a lot funnier than the subject implies and a whole lot funnier than about 90% of what gets called "comedy."

The movie asks the main character, Ben Tyler (Joshua Jackson), what he would do when his doctor tells him, "I'm afraid it's not great news." Tyler learns he has terminal cancer with a "survival rate of one in ten" and an undetermined "minimum" lifetime. [Something that is true for any of us all the time.] On his way home from the doctor's office, Tyler meets an old geezer polishing up his 1973 Norton to sell because "my eyes are going, I couldn't get my license renewed."(Move to Minnesota. Anyone can pass our state's eye exam.)

The bike wasn't entirely a spontaneous decision, as "Ben had been circling around the purchase for a while" because his fiancée had told him that "driving a motorcycle represented the height of stupidity." After one of the weirdest haggling scenes in movie history, Ben says, "I'll take it."

Ben's fiancée Samantha (brilliantly played by Liana Balaban) walks a fine balance between loving, overbearing, and wounded. Her hatred of motorcycles, desperate faith in the miracles of modern medicine, and her desire not to be the woman who abandoned her boyfriend when he got cancer all blend into a complicated character you'll either like or hate; or both. My opinion of her swung from one side to the opposite in practically every scene.

Ben decides to postpone his wedding, blow off his mind-deadening grade school teaching job, and obey the instructions on his coffee cup and "go west young man." At a loss for what to do with the end of his life, Ben sets out on a bucket-list trip from Toronto to British Columbia with a minor goal of seeing all the “big things” along the way; big chairs, biggest fake dinosaur, biggest paper clip, etc.

Ben tells Samantha he’ll only be gone two days, but his real plan is to travel without a plan or a schedule. All he knows about his future is that he’s “not ready to be a patient.” Ben doesn't tell his family or employer anything. Just before he takes off on his trip, he and Samantha participate in Ben's father's 70th birthday party where Ben's dad gives thanks for his uneventful life and his good fortune. Ben doesn't ruin the moment with his depressing news.

One of the many things I was reminded of by One Week is how much I love travelling in Canada. The camera work is terrific, the music selected for the movie is innovative and sets a high bar for indie productions, and the sound quality was as good as modern movies get. There is nothing in this production to get between you and the story. In my opinion, it is as flawless a movie as I have ever experienced.

Ben's relationship with the Norton, while exceptionally lucky (based on my experience with British vehicles), is dead on the money. He was almost as perfectly unprepared for this cross-country trip as he was for his medical prognosis. Riding into the Canadian sunset in jeans, a designer leather jacket, and an open face helmet, Ben is soaked, frozen, bathed in warmth and light, and bashed about by the trip and the people he meets. You will be, too.

All Rights Reserved © "Never argue with a fool; onlookers may not be able to tell the difference."

- Mark Twain I check the comments on this blog regularly. The idea is that we're going to have a conversation about the ideas I've presented. You should be aware of the fact that when someone emails me an interesting comment, the odds are good that I'll post that in the comments anonymously and reply to that comment on the blog rather than in email.

Dec 25, 2011

Dec 21, 2011

Doin' It for 45 Years?

If you read my last Geezer column in MMM, you know I've been on the tipping point for a hip replacement for a couple of years. I tipped over last week and had the old hip cut out and replaced with what I hope is a high tech prosthetics. So, I'm stuck in the house suffering the great views of a warm Minnesota December while my bikes wither away in the garage. What to do?

So far, that's easy. I have a handful of physical therapy routines to work on, I upped my Netflix DVD allowance so that I can choke on all of the western movies I can't get on-line, and I'm too doped up on morphine and oxycodone-actetaminophen to worry about anything for long. One of the movies that passed a bit of time was "Bustin' Down the Door," a documentary about the origins of pro surfing in the 1970's when the Aussies took the sport away from Hawaiian control and surfing went big-time worldwide.

There are two motorcycling-similar stories in "Bustin' Down." One was the reaction of the old-time, biker gangster types (called the "Black Shorts" and headed by a surfing Hell's Angel stereotype named Eddie Rothman in the film). Rothman and his gangbanger buddies view the beach and surfing as their territory and fought back against the Aussie invasion with the only tools they had; violence and intimidation. "If you can't beat 'em, beat 'em up" has been the gangbanger chant for centuries and, as usual, laws and the cops proved to be as useless in Hawaii as they are everywhere else. The gangbangers kept the Aussies out of championship events until 1975. The Aussies couldn't even get into major events in 1974. In 1975, they won every event they entered and major press attention (and big event purses) followed. Even in their own words, the Black Shorts characters were about preventing change, true conservatives. They wanted to maintain control of the dinky surfing pond they'd managed to create and the Aussies wanted to put surfing into the ocean. Literally, the Hawaiians were afraid to attempt the maneuvers the Aussies were introducing, so their solution was to chase the Aussies out of the sport.

In the end, the Black Shorts sort of won. Hawaii is no longer the hub of surfing. The Harley gangsters managed to pull of the same kind of coup in the US. By creating "Harley-only" race venues and through rules and intimidation, the 1960's US motorcycling gangsters drove anyone who wasn't a gangbanger to the other side. Today, the US makes marginally functional hippobikes and practically every country in the industrialized world makes real motorcycles. The conservatives won and the nation lost.

The other similarity between motorcycling and surfing was pointed out by South African, Michael Tomson, "Very few people can look through their life, and say they've been doing something for 45 years. What have you been doing for 45 years? I will surf till I die."

Before this surgery, my wife tried to reconcile me to the possibility that I'm going to have to quit riding a motorcycle some time. "You can't ride forever." I can't live forever, either, but I can keep riding for a lot more years and you may as well assume that I will ride till I die.

So far, that's easy. I have a handful of physical therapy routines to work on, I upped my Netflix DVD allowance so that I can choke on all of the western movies I can't get on-line, and I'm too doped up on morphine and oxycodone-actetaminophen to worry about anything for long. One of the movies that passed a bit of time was "Bustin' Down the Door," a documentary about the origins of pro surfing in the 1970's when the Aussies took the sport away from Hawaiian control and surfing went big-time worldwide.

There are two motorcycling-similar stories in "Bustin' Down." One was the reaction of the old-time, biker gangster types (called the "Black Shorts" and headed by a surfing Hell's Angel stereotype named Eddie Rothman in the film). Rothman and his gangbanger buddies view the beach and surfing as their territory and fought back against the Aussie invasion with the only tools they had; violence and intimidation. "If you can't beat 'em, beat 'em up" has been the gangbanger chant for centuries and, as usual, laws and the cops proved to be as useless in Hawaii as they are everywhere else. The gangbangers kept the Aussies out of championship events until 1975. The Aussies couldn't even get into major events in 1974. In 1975, they won every event they entered and major press attention (and big event purses) followed. Even in their own words, the Black Shorts characters were about preventing change, true conservatives. They wanted to maintain control of the dinky surfing pond they'd managed to create and the Aussies wanted to put surfing into the ocean. Literally, the Hawaiians were afraid to attempt the maneuvers the Aussies were introducing, so their solution was to chase the Aussies out of the sport.

In the end, the Black Shorts sort of won. Hawaii is no longer the hub of surfing. The Harley gangsters managed to pull of the same kind of coup in the US. By creating "Harley-only" race venues and through rules and intimidation, the 1960's US motorcycling gangsters drove anyone who wasn't a gangbanger to the other side. Today, the US makes marginally functional hippobikes and practically every country in the industrialized world makes real motorcycles. The conservatives won and the nation lost.

The other similarity between motorcycling and surfing was pointed out by South African, Michael Tomson, "Very few people can look through their life, and say they've been doing something for 45 years. What have you been doing for 45 years? I will surf till I die."

Before this surgery, my wife tried to reconcile me to the possibility that I'm going to have to quit riding a motorcycle some time. "You can't ride forever." I can't live forever, either, but I can keep riding for a lot more years and you may as well assume that I will ride till I die.

Dec 13, 2011

'splain This

Patrick, the man who had no problem understanding why HD would market Ken and Barbie biker-thug-dollies wanted me to explain this. I don't see me wanting to own this bike, but I can see the . . . attraction. It seems like a logical extension to the passenger position on most sportbikes, doesn't it?

Dec 11, 2011

Left Speechless?

There aren't that many things that can leave me speechless, but everything associated with this Craig's List ad is wrong. The Hardly marketeers who commissioned this product should be traded to the Village People (The Village People don't have anything that worthless to exchange, so Hardly should just launch their marketing department in the general direction of whatever casino the Villagers are currently playing.). The cupcake who is selling this abomination should be jettisoned into the ocean from the national clown cannon (No, I don't care if it's a 12-yar-old-girl, but we all know it's not.). Even Mattel should take a hit in their micro-macho rating for packaging such a poofster product.

$350? Who says the economy is trashed? If this lamester can get $3 for this POS somebody has a lot of cash to trash. If I ran Hardly, I'd be buying all this crap up and burning it to recover whatever reputation the company has left.

$350? Who says the economy is trashed? If this lamester can get $3 for this POS somebody has a lot of cash to trash. If I ran Hardly, I'd be buying all this crap up and burning it to recover whatever reputation the company has left.

Dec 10, 2011

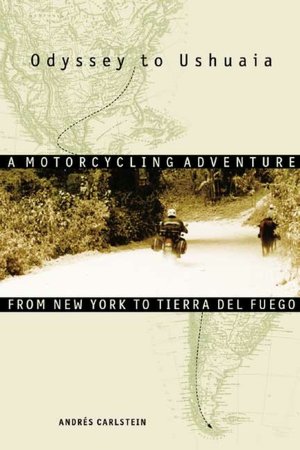

Book Review: Odyssey to Ushuaia

Odyssey to Ushuaia

by Andrés Carlstein, 2002

All Rights Reserved © 2011 Thomas W. Day

This is a tour story of a ride from New York City to Tierra Del Fuego, but it's an odd version of the usual saga of multi-national hardship and extreme sports because the main character, the author, is something of a flake. At the time of the trip (1999), Carlstein was 25 years old and mostly a rookie motorcyclist. He was fortunate enough to have stumbled (through Internet research) upon a KLR650 as his vehicle of choice, but every other thing he learned he had to learn the hard way.

Intentionally or otherwise, Carlstein portrays himself as an anti-hero. He is often childish, regularly selfish and callous toward the women he meets and the people who cross his path, and often arrogant. Honestly, I kept at the book to the end because I wanted to find something about this guy that I would like. To that end, I came away disappointed. I can't say I dislike Carlstein, as he portrays himself in his own book, but I wouldn't cross the street to meet him either.

To give you an idea of what it took to hammer my way to the conclusion, a few pages from the end Carlstein meets a pair of motorcyclists and gets into a discussion about Greg Frasier's South America tour book. Carlstein says Fraiser's book was "not bad." And explained that comment by noting, "I was trying to be nice. The book wasn't bad--when compared to a book that is terrible." Carlstein does that throughout the book. When you are almost starting to like him, he will find a way to make you feel that his many crashes, catastrophes, and personal problems are a just desert. As an author, he isn't a modern Shakesphere or even one who would challenge the skills of most newspaper writers. He is confident and you have to give him that.

Carlstein begins his trip on the right foot. Somehow, he manages to connect with two experienced long-range motorcyclists (Robert and Peter) and they meet in Texas just before the first international boarder crossing into Mexico. These two guys have the patience of near-saints while over the next several thousand miles they put up with a variety of screw-ups, mechanical problems due to Carlstein's general lack of motorcycle skills, and fairly regular temper tantrums. I liked both of those guys and half-wished one of them had written the book.

All three of these guys have South American connections and possess a variety of language skills, which serves them well through the disaster zones Central and South America call "boarder crossings." The best parts of Odyssey are when Carlstein is describing the places and people he meets on the road. The worst parts are the regular sections when he is feeling sorry for himself.

In the end, I found myself neutral on Odyssey to Ushuaia. It was a distraction during one of the longest winters of my life, but I can't say I'd ever read it again or recommend it to someone who wasn't equally desperate for a motorcycle book. If you don't have an unnatural desire to know as much as you can about South and Central American travel by motorcycle, I suspect you won't find much to like in Odyssey to Ushuaia. If you are considering this trip and want to hear what crossing those boarders is like, there might be some value in the book.

by Andrés Carlstein, 2002

All Rights Reserved © 2011 Thomas W. Day

This is a tour story of a ride from New York City to Tierra Del Fuego, but it's an odd version of the usual saga of multi-national hardship and extreme sports because the main character, the author, is something of a flake. At the time of the trip (1999), Carlstein was 25 years old and mostly a rookie motorcyclist. He was fortunate enough to have stumbled (through Internet research) upon a KLR650 as his vehicle of choice, but every other thing he learned he had to learn the hard way.

Intentionally or otherwise, Carlstein portrays himself as an anti-hero. He is often childish, regularly selfish and callous toward the women he meets and the people who cross his path, and often arrogant. Honestly, I kept at the book to the end because I wanted to find something about this guy that I would like. To that end, I came away disappointed. I can't say I dislike Carlstein, as he portrays himself in his own book, but I wouldn't cross the street to meet him either.

To give you an idea of what it took to hammer my way to the conclusion, a few pages from the end Carlstein meets a pair of motorcyclists and gets into a discussion about Greg Frasier's South America tour book. Carlstein says Fraiser's book was "not bad." And explained that comment by noting, "I was trying to be nice. The book wasn't bad--when compared to a book that is terrible." Carlstein does that throughout the book. When you are almost starting to like him, he will find a way to make you feel that his many crashes, catastrophes, and personal problems are a just desert. As an author, he isn't a modern Shakesphere or even one who would challenge the skills of most newspaper writers. He is confident and you have to give him that.

Carlstein begins his trip on the right foot. Somehow, he manages to connect with two experienced long-range motorcyclists (Robert and Peter) and they meet in Texas just before the first international boarder crossing into Mexico. These two guys have the patience of near-saints while over the next several thousand miles they put up with a variety of screw-ups, mechanical problems due to Carlstein's general lack of motorcycle skills, and fairly regular temper tantrums. I liked both of those guys and half-wished one of them had written the book.

All three of these guys have South American connections and possess a variety of language skills, which serves them well through the disaster zones Central and South America call "boarder crossings." The best parts of Odyssey are when Carlstein is describing the places and people he meets on the road. The worst parts are the regular sections when he is feeling sorry for himself.

In the end, I found myself neutral on Odyssey to Ushuaia. It was a distraction during one of the longest winters of my life, but I can't say I'd ever read it again or recommend it to someone who wasn't equally desperate for a motorcycle book. If you don't have an unnatural desire to know as much as you can about South and Central American travel by motorcycle, I suspect you won't find much to like in Odyssey to Ushuaia. If you are considering this trip and want to hear what crossing those boarders is like, there might be some value in the book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)